In the 1990’s, I worked as a programmer and a software developer. Back then, using computer software was quite difficult for the layperson. I moved into the field of interaction design and learned about usability in the 2000’s. It was a revelation: we could no longer blame the user for everything that went wrong with software – the blame now lay squarely with us, the ones who made the software.

The disciplines of usability and interaction design, along with several others, have since evolved into a field we now tend to call User Experience. We follow an approach called Human Centred Design, which involves ‘the human perspective in all steps of the problem-solving process’.

I have spent nearly a decade and a half working in this field and have always held a strong belief that design should be human centred.

Lately, I have been having some doubts. Let me explain.

Table of Contents

Human centred design is subordinate to business

Here’s what Jared Spool and Andy Budd have to say about the relationship between design and business:

There's only 5 things execs care about:

• Increasing revenues

• Decreasing costs

• Increasing new business/marketshare

• Increasing revenue from existing customers

• Increasing shareholder valueDesign leaders know to frame their team’s efforts as helping these priorities. pic.twitter.com/BR55Etarq1

— Jared Spool (@jmspool) February 9, 2018

When pitching new products, features or approaches, companies only really care about 3 things.

1. Does it make money?

2. Does it save money?

3. Does it reduce risk?So as designers we need to do a better job at positioning our work in relation to one of these three.

— Andy Budd (@andybudd) August 1, 2018

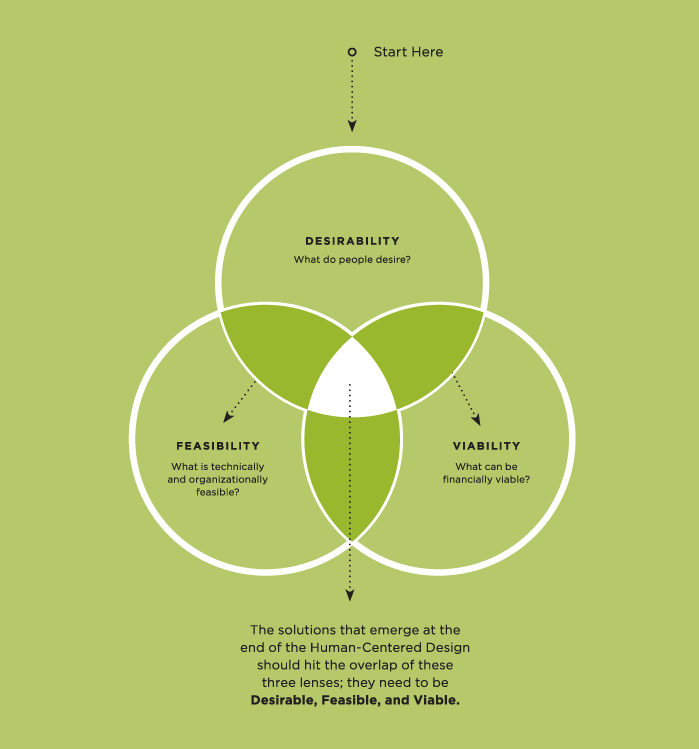

Business is integral to design, and I am under no illusion that design could be independent from business. This symbiosis is essential: one of the three key lenses in the classic IDEO design innovation model is ‘viability’, which refers to the financial viability of the product in question:

Don’t be fooled by symmetry of the diagram: business (viability) trumps both technology (feasibility) and design (desirability). Due to this dynamic, I recently came to this realisation:

Design at scale only exists in service of capitalism https://t.co/taznJLm3hB

— Jussi Pasanen (@jopas) October 11, 2018

This would be fine if capitalism was benign, however it is the opposite.

In recent years, designers have fought long and hard to ‘have a seat at the table’. In more experience-mature organisations we may now have that seat, however I am not convinced that we have an equal voice.

Since design is subordinate to business, the power asymmetry is such that a ‘human centred’ choice has virtually always less weight that a ‘profit centred’ one. This is why we have endless examples of products and experiences that are very well designed, yet not ultimately created in the best interest of the user.

Human centred design, centred on some

You may have read about techlash, the backlash against the technology giants that began in earnest last year, 2018. There are broad issues in technology being used to drive polarisation, amplify racial bias, increase inequality, even skew democratic elections. With seemingly endless violations of privacy, breaches of trust, and unbounded monetisation of our personal information, the technology industry has done much damage to itself.

Sadly, much of this is done with the willing participation of designers; designers who were just applying – and often expanding on – the ‘best practices‘ of our field. The design work at these technology firms follows a ‘human centred process’ and ‘improves the user experience’, yet the tech industry is reeling.

Virtually all of the services we used to celebrate as disruptive just a couple of years ago have significant negative structural impacts. Let’s look at just two examples.

Airbnb helps you ’find adventures nearby or in faraway places and access unique homes, experiences, and places around the world.’ The end-to-end experience is crafted, seamless and highly polished for the traveller and the host alike. It really is a pleasure to use.

Airbnb also skews housing affordability in many cities. It facilitates mass tourism with many negative impacts on local communities. It also increases demand for aviation and other carbon-intensive transport, consequently adding to global emissions and fuelling climate breakdown.

Uber is a ‘ridesharing app for fast, reliable rides in minutes’. Again, the experience is super convenient and very slick. Uber takes out the thinking from organising transport.

Uber considers its drivers ‘driver partners’ rather than employees to maximise flexibility and to avoid paying them employee benefits. At first glance, their service may appear like a marketplace, however it most certainly is not a real or a level one. Uber forces traditional taxi operators out of business, impacts drivers’ livelihoods, and increases traffic congestion in cities like New York.

Mexie captures many of these issues well in her critique of share-washing:

Human centred design has made digital products and services exponentially easier to use compared to the early days of computing. It has also made many daily interactions so much more seamless and convenient, especially for wealthier people.

However, not all humans are equal in the typical human centred design process. The customer who pays the bill gets a hand-crafted experience, whilst the broader society and the living planet are typically ignored – or even taken advantage of.

Human centred design is literally anthropocentric

Learning about the concept of anthropocentrism last year was a revelation:

Anthropocentrism is the belief that human beings are the most important entity in the universe.

Here’s a great explanation of anthropocentrism and why it is extremely problematic from Eileen Crist via John Thackara – please watch the whole 16-minute talk:

The anthropocentric world view is about dominion and having extra-human life and the rest of the planet reduced to mere resources, to be exploited by man at will. This belief underpins the ongoing destruction of the living planet we see all around the world today.

What does this have to do with design?

Human centred design is literally anthropocentric design.

By focusing only on humans, we frame out the rest of the living planet. Mountains, rivers, oceans, rivers, wildlife and other animals, insects, bacteria and the rest of the bio- and geosphere become irrelevant. If their destruction is required to improve the human experience, so be it. Nor does it matter if the problems we are ‘solving’ are real or manufactured.

In economist speak, all these natural wonders that enable and sustain life, are a mere externality. At best, they are just a backdrop, a temporary canvas or a prop for the perfect Instagram shot on a carefree long-haul holiday.

The era of human supremacy is coming to an end. We can no longer keep solving human problems at the expense of the living planet.

Beyond human centred design

When us designers make things more convenient for users, products easier to buy for customers, and customer service more frictionless, there is virtually always a business transaction that takes place behind the scenes. Something is being bought and sold.

When something is being bought, there is almost invariably a direct or an indirect component of extraction, exploitation or emissions to it. This is unavoidable in the system of industrial capitalism, for it is a system that is fundamentally unsustainable.

One of my core ethical principles with regards to user experience has been ‘doing things that are in the best interest of the user’. Sometimes this is easy to assess: if you are big tobacco, a gambling organisation, a payday lender, or another company directly exploiting your customers, you fail this principle automatically – no matter how ‘good’ your user experience is.

Other times it is not as clear cut. Consider something like Amazon Prime, a service that is ceaselessly filling the homes of millions of customers with stuff they don’t really need. I am sure it is a perfectly designed service, taking out some of the ‘pain’ of the mundane. But our consumption culture and industrial capitalism is fast taking us towards ecological and climate collapse. Once you realise this, you can ask: is Amazon Prime, surely one of the pinnacles of human centred design, really a service operating in the best interest of their customers? There is no convenience on a dead planet.

I recognise the role of human centred design in significantly improving the experiences of millions of people worldwide, especially when measured with the traditional metrics of ease-of-use, time-to-task, efficiency, productivity, reduced wait times, and even ‘delight’.

However, I am not seeing much conversation on this:

By tirelessly making commerce easier, faster and more convenient, and therefore increasing material consumption and driving growth, what is the role of human centred design in directly and indirectly facilitating the destruction of the living planet by being the carbon-stained ‘velvet glove for the iron fist’ of globalised capitalism?

Is now the time to start a conversation on this, and perhaps consider moving beyond human centred design?

References

- Hero image: Checking the phone on the plane by Javier Cañada

- Wikipedia: Human-centered design

- Jussi Pasanen: Undo capitalism or it will undo us

- UX Collective: Design is not saving the world

- ABC: Airbnb not significantly hurting rental affordability in Sydney and Melbourne, report reveals

- Gaby Hinsliff in The Guardian: Airbnb and the so-called sharing economy is hollowing out our cities

- Forbes: Are Uber Drivers Employees? The Answer Will Shape The Sharing Economy

- Anil Dash: Tech and the Fake Market tactic

- Bruce Schaller: The New Automobility: Lyft, Uber and the Future of American Cities

- Mexie: The Share-Washing of Late Stage Capitalism

- Wikipedia: Anthropocentrism

- John Thackara on Twitter: ‘I’ve never liked the #anthropocene meme but could not explain why. This brilliant short talk by Eileen Crist explains why “the cultural conditioning of the human” is at the heart of what we have to change’

- Eileen Crist: Confronting Anthropocentrism

- Jussi Pasanen: We are mistaking wants for needs and it is costing us the world

- Eileen Crist: Reimagining the human

- Jussi Pasanen: The downsides of convenience

- Jussi Pasanen: On embodied emissions, exploitation and the unsustainability of consumer products

- Jussi Pasanen: Collapse: You cannot prepare for what remains unthinkable

- Lilly Irani on Catalyst Journal: View of “Design Thinking”: Defending Silicon Valley at the Apex of Global Labor Hierarchies

- Cassie Robinson: Beyond human-centred design, to?

Related

- Jesse Weaver: Design Won’t Save the World

- Alison J. Clarke in Metropolis Magazine: Design Provocateur: Revisiting the Prescient Ideas of Victor Papanek

- This is HCD interview with John Thackara: Designing for all of life, not just human life (Added 1 Feb 2019)

Thanks to everyone who reviewed versions of this essay.

Update (May 2019)

The slides for my talk on this topic are now available:

Update (Feb 2020)

Gerry McGovern kindly posted this essay on Twitter and sparked a broad conversation. Please read the whole winding thread for comments from him, Jared Spool, Andy Budd, Andy Polaine, Alan Cooper and many others:

I have spent nearly a decade and a half working in this field and have always held a strong belief that design should be human centred. Lately, I have been having some doubts. Let me explain. https://t.co/VrSoN76ziw – Great piece — a very important read

— Gerry McGovern (@gerrymcgovern) February 19, 2020