I have been thinking about change.

Specifically, I have been thinking about the difference between individual change and system change. These terms are prevalent in the climate change discourse, and often presented as a black-and-white, mutually exclusive choice. This is a false dichotomy.

Note: This essay is me thinking aloud and it is not based on any formal theory of change. I would love to hear your feedback, and any pointers to recommended reading and research.

Table of Contents

Individual change

There are many good arguments for why individual change alone is insufficient. There is no doubt that neoliberalism really has conned us into ‘fighting’ climate change as individuals. It’s the same old story of the Crying Indian, litterbugs, Keeping America Beautiful and any number of other examples of corporate co-optation.

One can argue that Recycling too is a con job, designed to distract us from the much more important actions of Reducing and Reusing. Corporations go to great lengths to manipulate the conversation, injecting FUD and continuing business as usual.

Not only is individual action insufficient – it can even be counterproductive. This is what happens when the energy we expend on individual change is energy away from organising, demanding and agitating for system change.

Jane Morton puts it really well in this episode of Greening The Apocalypse – listen from the 38:30 mark:

Beware the individual solution. …

Don’t wear yourself out doing individual things, when you could use that energy to win a big political battle.

–Jane Morton

This is not to say that individual change is not important, it most certainly is. But it should not be the only change.

System change

System change is tricky, too. As a term, ‘system change’ is vague and quite neutral, which makes it too open to co-optation. Let’s look at an example: Lots of people going to climate marches today carry a sign stating ‘System change not climate change.’ Sounds good right, but what does is really mean?

One interpretation is that it is demanding a change in the existing system – late stage capitalism – for example to be more ‘sustainable’ (a term that itself has been co-opted to the point that it has become meaningless).

This is the capitalist’s favourite version, as it calls for a minor adjustment, which can be countered easily. For instance, if you convert a factory churning out 100,000 soft toys per a day to run on renewable energy, the system has been ‘changed’, and it is now a bit more ‘sustainable’ isn’t it? Job done.

Another reading is that system change means a change from the current system to another system altogether – let’s call this system replacement. For instance, some are calling for a wholesale transition from late stage capitalism into ecosocialism.

The current system does not like this, because the its number one goal is to uphold and grow itself. However, again, there is a within-system solution: reform. Unfortunately, reform is often only an illusion of change, one where the original power structures continue virtually uninterrupted behind the scenes.

Here’s how the Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors (an organisation for which replacing the system would be an existential risk, ironically) explain the difference:

The first step towards achieving systems change: Agreeing on a common definition

…

we are seeking to clarify the difference between changing a system (e.g., education or climate change) and The System (the entirety of the system we live within, for example the patriarchy or capitalism).

To summarise: When we talk about system change it can mean the following:

- A system change of, and within, the existing system, or

- A change from the existing system to another system – a system replacement.

Late stage capitalism has mechanisms to subvert both demands. These mechanisms must be identified and countered to make change possible.

Bridging individual change and system change

Going back to the broader question of individual change vs. system change, let’s go through a thought experiment starting with the following assumptions:

- Humans are social beings

- Individual people group into collectives

- System change, and system replacement, can only happen through collective efforts.

Therefore, system change can only be instigated through the coordinated efforts of individuals.

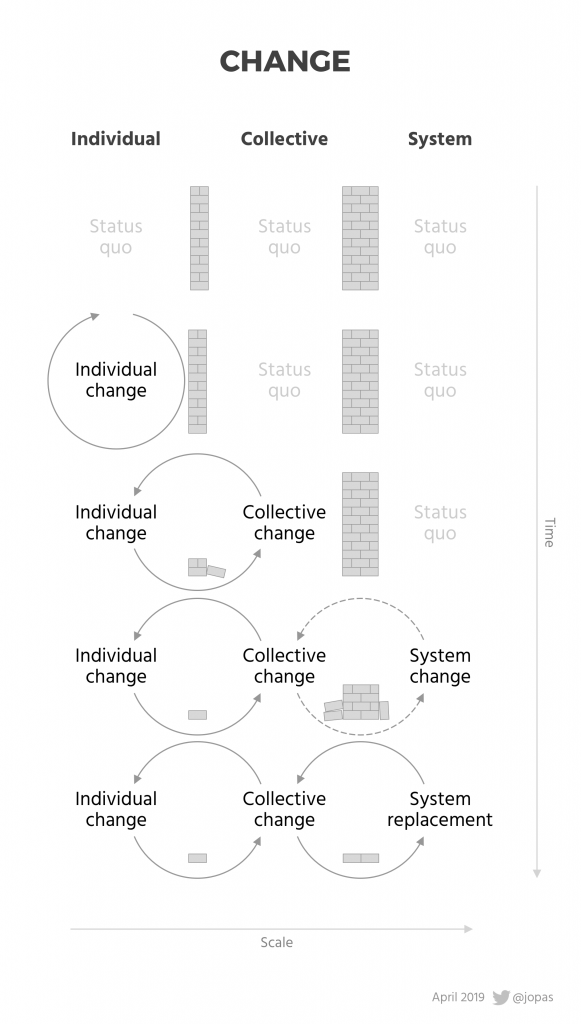

I’ve tried to illustrate this in the following diagram:

About the diagram:

- This diagram illustrates system change and system replacement. However, it does not consider the even more complex case of changing or replacing multiple intertwined systems together; something that could be called systems change or systems replacement, in plural.

- Change means changing the power balance, which requires energy. Status quo means maintaining the entrenched power unchanged.

- An individual can recognise the need for change, and make a change in their own life. However, without exemplifying or communicating this to their social groups – collectives – this will have very limited impact.

- An individual can recognise the need to change, without making a change in their own life. They can still demand collective or system change. (Whether it is right to demand change of others without changing yourself is a separate, complex topic. See also: Skin in the Game)

- For certain things, an individual can recognise the need but is prevented from making any immediate change in their own life towards that change. For instance, you can demand (more) nuclear power but the only way to achieve that is building collective and system change over time.

- Even though the diagram implies a hierarchy, it is really more like a network. For instance, separate collectives may be only loosely aligned but still agitate towards the same broader system change or replacement.

- Change is bidirectional: For instance, when an individual is pushing for a change in a collective, the collective will also impart change (and resistance) on the individual.

- The larger the scale, then more inertia and the higher the barrier to shift the status quo. This is indicated by the brick walls in the diagram.

- The dotted line and the remaining barrier between collective change and system change indicate that system change is partial. It also almost never ‘complete’ when measured against the original intent.

- Modern societal systems, by definition, are extremely large and complex. Therefore, they can only be shifted by the joint efforts of a large number of collectives.

- This diagram considers change as demanded by the less powerful (e.g. individual) of the more powerful (e.g. system). By definition, the system has a power advantage and can force change on collectives and individuals, often with little consultation or justification (e.g. increased authoritarianism or surveillance, decreased privacy, and so forth).

A hypothesis

My core hypothesis here is this: There cannot be system change without individual and collective change first. Therefore, the choice is not binary but rather a journey that starts from individual change.

As a person, you don’t really choose between individual change and system change. Rather, you choose to:

- Pay enough attention to become aware of a problem or a predicament (or not)

- Take the time to develop an understanding of the predicament and its context (or not)

- Do something about it yourself, in your own life (or not)

- Demand and instigate change in others (or not).

With the right problem, understanding, circumstances and organising, you can become an active part of a collective. Your collective can align with other collectives, and together coordinate a push for system change or replacement.

That said, most individual change or collective change will not lead to system change or replacement – the entrenched power is too strong. To break through the increasingly high barriers of inertia and proactive resistance by the system, collective change needs to be strategic, highly coordinated, multifaceted, and persistent over a long period of time. Only then can it become system change and, perhaps, system replacement.

System change it possible when enough people share an understanding of a problem, have a similar view on what needs to change, and take a coordinated journey in the same direction.

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.

–Margaret Mead

References

- Samuel Miller-McDonald in The Trouble: What We Should Really Do For the Climate

- Martin Lukacs in The Guardian: Neoliberalism has conned us into fighting climate change as individuals

- Finis Dunaway in Chicago Tribune: The ‘Crying Indian’ ad that fooled the environmental movement

- 99% Invisible: National Sword

- Commercial partners of Keep America Beautiful

- Wikipedia: Fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD)

- Jussi Pasanen: Business as usual is killing the planet“

- Jane Morton: Climate Emergency Declaration

- Greening The Apocalypse on RRR FM, 6 Nov 2018: Emergency Climate Action, with Jane Morton

- VGP Channel: Soft Toys Production

- SCNCC is a network of North American ecosocialists: System Change Not Climate Change

- Darren Allen on OffGuardian: The Myth of Reform, an extract from 33 Myths of the System

- Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors: We Need to Talk about Systems Change

- Nassim Nicholas Taleb (2018): Skin in the Game

- Brian Davey on Resilience: Anticipating the Coming of Troubles – Envisaging a Lifeboat Economy (see quote from Chris Martenson on problems vs. predicaments)

- Endnote: I am not familiar with Margaret Mead’s work but sounds like it’s not without controversy: Sex, Lies, and Separating Science From Ideology

Related

- Kevin Anderson: A succinct account of my view on individual and collective action

- Julia Steinberger: An Audacious Toolkit: Actions Against Climate Breakdown (Part 3: I is for Individual)

Thanks to everyone who reviewed versions of this essay.